Lots of acts flew in the Las Vegas of the ’70s and ‘80s that wouldn’t today. But Bobby Berosini’s Orangutans barely survived that period.

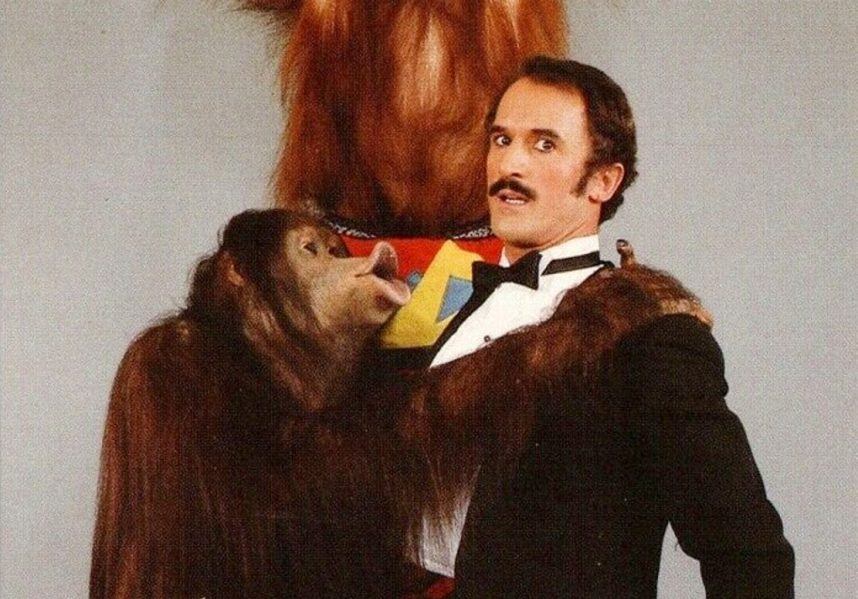

Berosini trained orangutans to behave like humans in Las Vegas a stage act in which he played their straight man. The dialog was strictly vaudevillian, meaning not funny today at all. Here’s a representative sample…

“For your information, folks, that’s not an orangutan. That’s a mean hooker. I picked her up at the bar last night. She washed her makeup off and this was underneath it. What do you expect for $1.98?”

But it wasn’t cringeworthy jokes that cost Berosini his career. We’ll get to that in a minute.

Orangutan Crazy

Berosini was born Bohumil Berousek into a circus family that had performed together since 1756. Fourth-generation member Hynek Ignac Berousek, a bear-tamer, formed Cirkus Berousek in 1920. It was taken over by his son, Antonin, who was Berosini’s father.

Berosini and Antonin emigrated to the US in 1964. They made their way to Las Vegas, where they collected a literal zoo of wild animals that they used their circus experience to train. Due to their impressive intelligence and ability to emote, their orangutans proved to be the best fit for comedy.

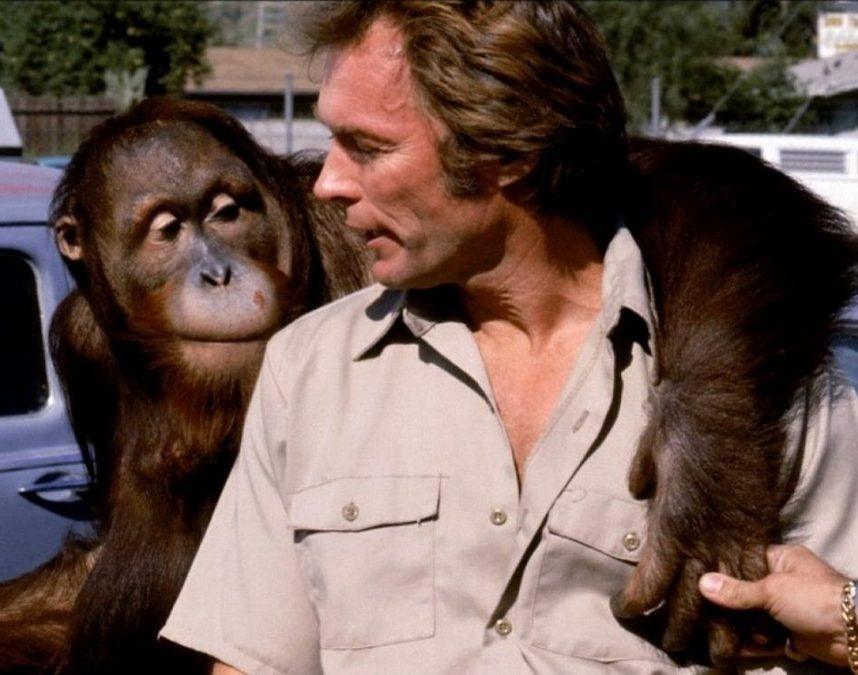

“Bobby Berosini’s Orangutans” premiered at Circus Circus in 1972, where the show became such a hit, Hollywood beckoned. In 1978, one of Berosini’s orangutans, Manis, starred (as Clyde) alongside Clint Eastwood in the 1978 comedy “Every Which Way But Loose.” Three years later, several joined Tony Danza and Danny DeVito in the movie “Going Ape!”

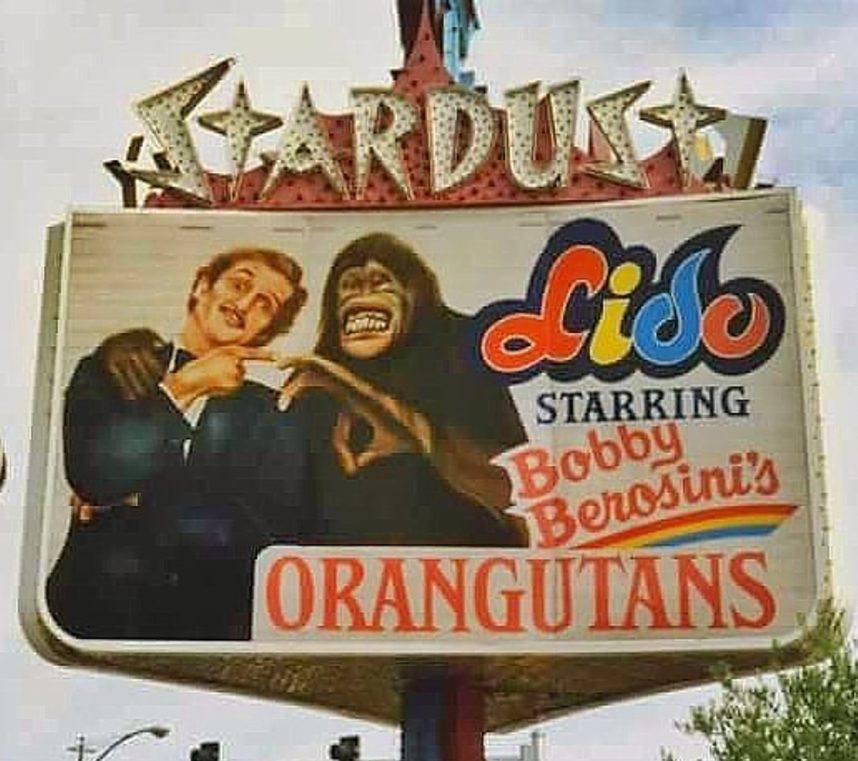

In 1984, the same year Berosini’s apes appeared in “Cannonball Run II,” the Stardust stole Berosini from Circus Circus and made his act a twice-nightly feature of its “Lido de Paris” showgirl/variety show.

Here’s how a typical performance looked…

Apes**t Hits Fan

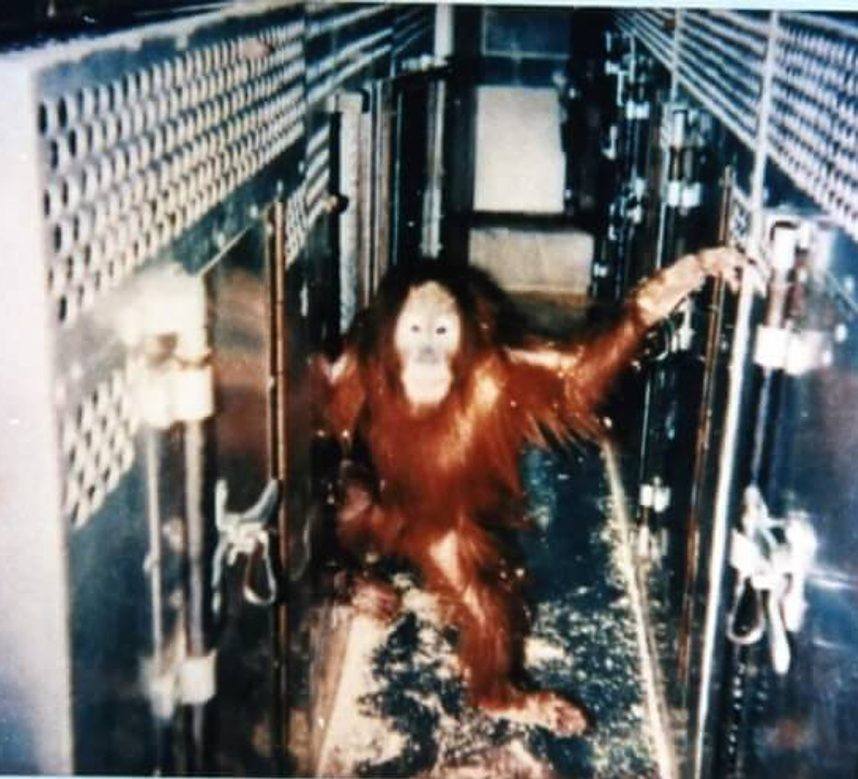

In 1989, Stardust dancer Ottavio Gesmundo secretly videotaped Berosini punching, slapping and shoving one of his orangutans while helpers held the animal by the arms.

Allegations of abuse stretch back to 1972, when Circus Circus employee Linda Faso noticed distressing sounds emanating from Berosini’s trailer immediately preceding each day’s lunchtime performance. Faso later said she reported her concerns to casino management, only to be told that the animals were Berosini’s property to do with as he wished.

Gesmundo and several of his fellow dancers also suspected abuse. After hitting a similar management wall at the Stardust, Germundo, armed with a new Super 8 camera, shot some dark and grainy footage that, for the first time, proved it.

He sent it to People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and the Performing Animal Welfare Society (PAWS).

A member of PAWS brought it to “Entertainment Tonight,” which broadcast it to the world on July 27, 1989. The video is age-restricted and, therefore, can only be viewed on YouTube itself.

The resulting blowback generated more than 1,000 out-of-state protest calls to the Stardust. The resort canceled Berosini, but only for a few days. An investigation by the US Department of Agriculture found no evidence of harm, so Berosini and his orangutans were allowed to return to “Lido.” The act lasted until the show closed in 1991, then moved on to the Stardust’s follow-up show, “Enter the Night,” for several more years.

The damage to Berosini’s reputation had already been done, however.

Monkey Trial

Claiming that he was videotaped merely “correcting” his co-stars, Berosini sued Gesmundo, PETA and PAWS for defamation and invasion of privacy in 1989. A year later, a jury found in favor of Berosini, awarding him $4.2 million in damages.

“Thank you, America,” Berosini told reporters as he left the courtroom.

Four years later, however, that judgement was overturned by the Nevada Supreme Court, which ruled that the tape was an accurate portrayal of Berosini’s behavior and, therefore, fell within the realm of protected opinion. This judgment was affirmed on a rehearing a year later, and in 1996, a Nevada District Court judge ordered Berosini to pay PETA and PAWS $417,000 in attorneys’ fees.

By then, sensibilities regarding the exploitation of wild animals for human amusement had already begun to shift. In 1993, Berosini told Harper’s Magazine that he and his wife received multiple death threats. He said they also shopped at a different supermarket every day due to threats that the orangutans’ food would be poisoned.

Berosini took his act to Branson, Mo., hoping for a fresh start. In 1997, he made his final Las Vegas appearance, offering up his orangutans for photo-ops at the Tropicana. But pressure from PETA forced the casino resort to cancel his contract.

Berosini and his wife eventually left the US. They are believed to be living in Costa Rica.

Before leaving, they reportedly sent their orangutans to an unidentified Hollywood training compound.

Popi — who appeared in “Going Ape!” and as the girlfriend of “Clyde” in “Any Which Way You Can,” the 1980 sequel to “Every Which Way But Loose” — was moved from there in 2008 to the Great Ape Trust, a cognitive research facility in Iowa. That facility sent her to Florida’s Center for Great Apes, an accredited sanctuary, in 2012, where she remains today.

In April, Popi celebrated her 53rd birthday, making her the second-oldest Bornean orangutan in North America.

The post LOST VEGAS: Bobby Berosini’s Orangutans appeared first on Casino.org.