An infinite amount of work can go into crafting a high-quality cocktail, from the basics of using fresh juice and good ice to the painstaking complexities of things like house-made infusions, clarification, and force carbonation. But, ultimately, only a very small percentage of guests at any given bar will be there primarily to taste that labor of love. Even in the most technique-driven bars there are dozens of Vodka Soda drinkers every night, only there because they enjoy the room or got dragged there by their weird cocktail friend (we love you, weird cocktail friend). There’s nothing wrong with someone ordering the drink that makes them happy at a bar, and on a busy night a Vodka Soda can be a godsend to a weeded bartender in a busy service well. But a long string of off-menu one-and-ones can lead to some nagging questions. Namely, who is all this work for?

The joy of writing this column has been the opportunity to connect with bartenders who share a common thread: The work they do is not for any kind of external validation. It’s driven by a hunger to make the most delicious drinks possible — a switch in their brains that’s permanently stuck in the “ON” position that demands going the extra mile in pursuit of beverage excellence. The work is joyful and fulfilling because it brings joy and fulfillment to the individual, regardless of whether guests realize the true extent of the work involved. It’s not just happening in big markets — thanks to the proliferation of social media and traditional media with a focus on cocktails, bartenders have no need to move to one of the major cocktail cities like New York, London, or Tokyo in order to access cutting-edge techniques. Great drinks are being served in more places than ever.

One such bartender, pushing the boundaries in a market not known traditionally as a cocktail hub, is Miles Macquarrie of Kimball House in Decatur, Ga. Meeting Miles, I was immediately thrilled to find that his particular hard wiring toward delicious drinks so closely mirrors my own, leaving no technological stone unturned in pursuit of superior cocktails. In addition to the old stalwarts centrifuge clarification and force carbonation, Miles is breaking ground in the realm of vacuum distillation, using a rotary evaporator to make hydrosols and utilizing them as dilution in outrageously flavorful freezer Martinis.

High Tech With Purpose

Within the first few minutes of my chat with Miles, we were discussing brand preferences regarding laboratory centrifuges for bar use (he likes Beckman Coulter; all my experience is with Jouan) and I knew I had found someone I could vibe with on a molecular level. His dedication to thoughtful cocktails is obvious but not overbearing, as evidenced by the fact that Kimball House just celebrated its 11th anniversary, an impressive milestone for any food business, especially a restaurant whose primary driver of beverage sales comes from spirits and cocktails rather than beer and wine.

The success of Kimball House’s cocktail program is a result of not relying too heavily on any particular dogma, Miles says. Instead, he adopts a three-pronged approach, leaning on the Sasha Petraske-style classic focus for cocktail service, a Dave Arnold mindset for prep, and a commitment to weekly delivery from local farms and using produce from the restaurant’s own garden. “If we had to choose between perfectly executed classic cocktails and all this high-tech stuff, we would go the classic route. But fortunately we don’t have to make that choice,” he says.

We could have talked for hours about the nitty gritty of any number of drink techniques, but for this interview we focused on something that Miles has been devoting a great deal of mental energy and prep hours toward: drinks he’s calling hydrosol Martinis.

Vacuum Distillation 101

To craft these Martinis, Miles relies on an advanced piece of laboratory equipment called a rotary evaporator, or “rotovap.” It’s gained a lot of traction in the cocktail world in the past 15 years or so, especially abroad where laws around distillation are much more forgiving. The most basic description of the device is that it’s a still that’s small enough to sit on a tabletop, and the entire system operates under vacuum pressure.

Traditional distillation — how most spirits are made — relies on heating a liquid to its boiling point so that lighter molecules like flavor and aroma (and alcohol) evaporate and are then chilled and condensed back into a liquid in a different chamber. But the vacuum pressure of a rotovap lowers the boiling point of any liquid to near room temperature. That’s an important distinction because the flavor and aroma of a liquid that’s been heated to 212 degrees Fahrenheit is drastically different from a product that’s never been cooked. A rotovap provides the opportunity to capture and condense the pure aromatic essence of an ingredient in a water-based liquid called a hydrosol.

Hydrosols are very common in the cosmetics, beauty, and fragrance industries, but are underexplored in culinary applications outside of classic examples like rose water and orange flower water. It’s very important to note that Miles and Kimball House exclusively use their rotovap to make hydrosols (i.e., distilling non-alcoholic base ingredients). It remains federally illegal to distill alcohol at any establishment without a specific license to do so, which is also a major reason bars in Europe and Asia are lapping the U.S. when it comes to rotovap utilization.

Hydrosols in Practice

One of Miles’s early experiments involved spent lime juice from the previous service. Vacuum distilling the citrus produced a liquid that he describes as a “a flat, highly flavored lime LaCroix” — not necessarily the most useful product but an interesting case study that got Miles’s brain working.

The next experiment was an immediate winner. He distilled fresh cucumber juice into the pure essence of cucumber, then used that hydrosol for the dilution component in a batched Martini. The drink arrives in the coupe freezer-cold, and as Miles describes it, “really cooling and refreshing yet still very familiar and stiff and lean.” It’s a cocktail Kimball House only occasionally features as a special, because the process takes about four hours to yield just 2 liters of hydrosol. At a standard 2 ounces of dilution per cocktail that’s four hours of prep to make 33 drinks. That might sound like a lot for home use, but it could easily be gone in a single service at a busy bar.

The cucumber hydrosol Martini eventually evolved into the Garden Vesper, a series of cocktail specials that highlights the produce from Kimball House’s garden. The cocktail uses hydrosols as a flavor component rather than the entirety of the dilution, which allows for its inclusion on the menu. They’ll choose an ingredient from the garden and a gin that pairs well with it — lemon thyme and Plymouth, for instance — and combine them into a hyper-focused Vesper variation. The lemon thyme is blended with water and distilled into a hydrosol, then married with vodka to make a heady, ethereal infusion. The Plymouth, lemon thyme vodka, and a combination of vermouths are stirred together to create a terroir-driven Martini.

Miles is nowhere near done experimenting with hydrosols. He gave me a video tour of his lab corner of Kimball House’s kitchen and talked me through other experiments, including Coca-Cola and marigold leaf hydrosols waiting for a home in a cocktail. It was at this point that I was officially ready to book a plane ticket. Decatur is a cocktail destination and Kimball House is the epicenter.

*Almost* Try it at Home

For the very few who have access to a rotovap and can replicate the real thing, Miles keeps his water bath between 35 and 40 degrees Celsius and his condenser at 0 degrees Celsius. He drops the pressure in the system to around 25 millibars during the actual distillation run. If you’re looking for ingredient inspiration, we found incredible results with a Naga Jolokia (ghost pepper) hydrosol at Booker and Dax. All the floral, fruity pepper flavor with none of the punishing heat. You just have to be sure to thoroughly clean everything afterward, and not breathe the fumes from the blender when you blend the peppers before distillation.

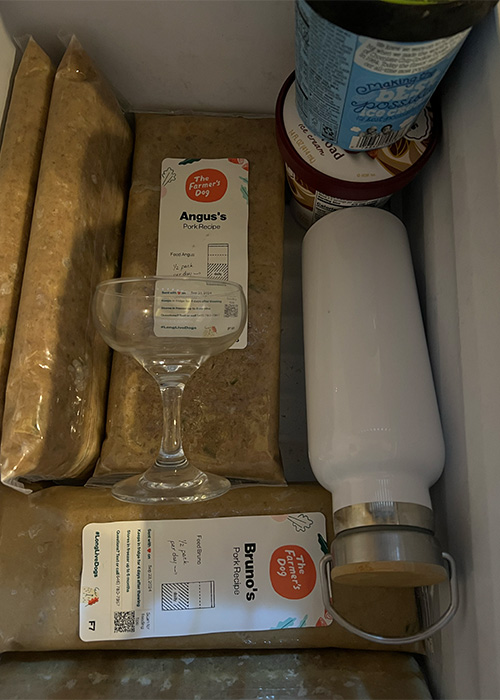

While most home (and professional) bartenders don’t have access to a rotovap, using a flavorful liquid for dilution in a batched Martini is easily replicable, so I came up with an alternative. When I worked at the NoMad Bar, bar director (now partner) Leo Robitschek put a cocktail on the menu called the Detox Retox, a Scotch Old Fashioned that replaced some of the dilution with coconut water. I try to only steal from the best, so I created this freezer Martini that replaces plain water or hydrosol with coconut water. It’s rich and round but with biting acidity from a touch of yuzu cordial. I chose Vestal Unfiltered potato vodka as a base. It’s my all-time favorite vodka and drinks more like a potato eau de vie. If you can’t find it, a high-quality sweet potato shochu is a good substitution.

Coconut Yuzu Martini

Ingredients

- 2 ounces Vestal Unfiltered vodka

- 2 ounces Harmless Harvest Coconut Water

- 1 ounce Method Dry Vermouth

- ¼ ounce yuzu cordial* (recipe below)

Directions

- Add all ingredients to a single-walled stainless steel or glass bottle.

- Freeze for at least an hour until the liquid is well chilled.

- Pour into a frozen coupe and serve.

*Yuzu Cordial Recipe

Ingredients

- 650 grams yuzu juice (bottled is fine)

- 650 grams sugar

- 75 grams lemon peels (or yuzu peels if you’re using fresh)

- 22 grams citric acid

Directions

Add lemon juice, sugar, and peels to a saucepan over medium heat. Stir to make sure the sugar dissolves and doesn’t stick to the bottom of the pan. Stir regularly and keep a close eye on the pan so it doesn’t overheat. As soon as the mixture hits a bare simmer, turn off the heat and allow it to cool. Strain the syrup to remove the peels. You should have 1 liter of syrup. For every liter of syrup, add 22 grams of citric acid.

The article Hydrosol Martinis and Vacuum Distillation With Miles Macquarrie of Kimball House appeared first on VinePair.