The Grand Seiko Media Experience is a whirlwind tour of several Grand Seiko/Seiko facilities across Japan. It’s designed to immerse journalists with a precursory knowledge of the brand in its culture, capabilities, processes, and goods while also giving a flavor of Japan itself. As one of four media invited to go last fall from the US and UK, I was delighted by the opportunity, but my goals were different, I believe, than those of my fellow attendees. You see, I am what you might call a Grand Seiko nerd.

I have reviewed several of their watches (such as the Snowflake and White Birch), served on a panel of their GS9 event, espoused my affection for the brand in a video with fellow Worn & Wound colleagues, and, perhaps most importantly, owned several of their timepieces (and still do). My goal during this trip was less to learn about the brand, though any information I could gleam would be valued, rather to further my appreciation for their craft and better understand the people who put my (and your) watches together.

Now, I could take you through each stop we made, every meeting we had, and each lecture or interview from an esteemed member of the Grand Seiko and Seiko ranks (including Mr. Hattori) we took, but I feel that article has been written. Instead, I want to tell you about how it affected me from the perspective of the Grand Seiko enthusiast I claim to be. And there will be lots of photos to show the rest.

The journey started and ended in Tokyo, a suitable place both for a trip to Japan (of which this was my first) and for one revolving around Grand Seiko and Seiko. The Seiko House Ginza, formerly Wako building, stands at an intersection of the heart of the neighborhood to which it shares its name. An old building that has been rebuilt and modernized a few times over the last century and more, it is a landmark of the area with its iconic clocktower and a fitting heart for the company (it was also under construction at the time, hence the lack of an establishing photo).

This was the first thing I learned: Seiko is still very much a brand with heart, literally and figuratively. It struck me the first day upon meeting with the team that was giving us the tour, as well as various executives, including Mr. Naito, the president of Seiko, and Mr. Hattori, the Chairman, Group CEO, and Group CCO of Seiko Group Corporation, and direct descendant of company founder Kintaro Hattori. It was palpable in the Seiko Museum Ginza and continued as a thread through the trip to the Shinshu and Shizukuishi manufacturing and assembling facilities.

During our stay in Tokyo, we visited the new Atelier Ginza, located within the Seiko House Ginza and where the Grand Seiko Kodo Constant Force Tourbillon is assembled. A prize of the brand, the movement’s designer helms the new studio, Mr. Takuma Kawauchiya, who gave us a walk-through of the watch and movement, something I’ve had the pleasure of experiencing more than once. In terms of the experience overall, it was a curious place to begin.

The Kodo is far beyond Grand Seiko’s fundamentals in concept and price. A proof-of-concept in practice, it shows the company’s capabilities while also making a statement about its willingness to pursue innovation in terms of engineering and aesthetics. That a relatively young watchmaker helms it makes a statement as well. Though a logical place to begin given its location, showing us the Kodo and the company’s newest studio first, it planted into our minds that Grand Seiko, despite its at-times-traditional trappings, is a brand with its eyes on the future.

“Always one step ahead of the rest” is Seiko’s slogan. It’s a saying that I heard repeated many times throughout the trip and one I’ve been thinking about since. There are ways, such as with the Kodo, Spring Drive, and the 9SA5, that Grand Seiko feels several steps ahead, yet they see themselves as just one. Perhaps that is a form of modesty or a way to keep the brand grounded. Admittedly, there are times when they seem the opposite too.

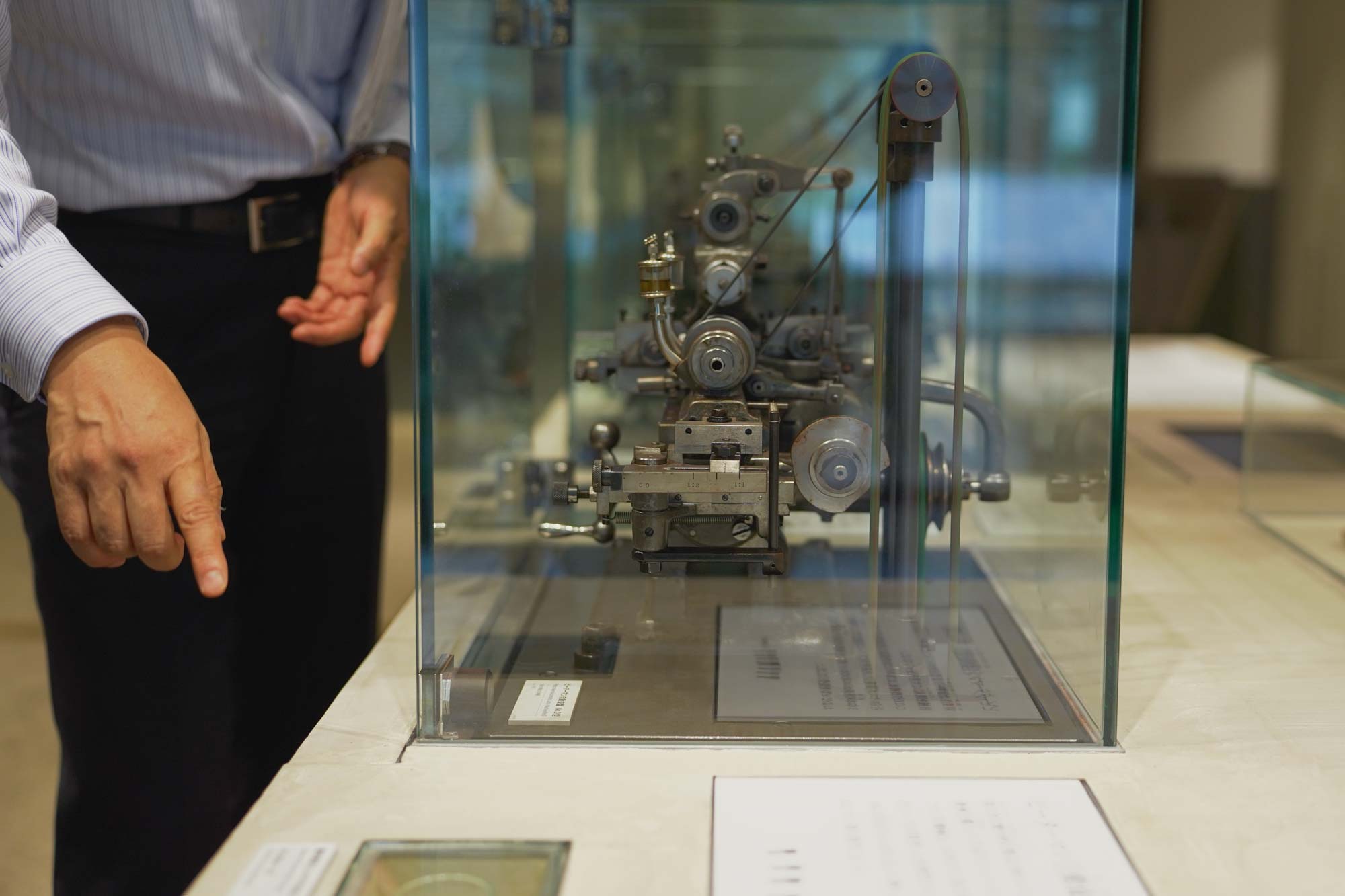

In contrast to the Atelier Ginza, we visited the Seiko Museum Ginza, which gets to the company’s roots and timekeeping. An unexpected highlight of the trip, the museum contained examples of Seiko watches and clocks ranging from the company’s beginning to modern times. But two things stood out to me there. The first was a lump of melted pocket watches.

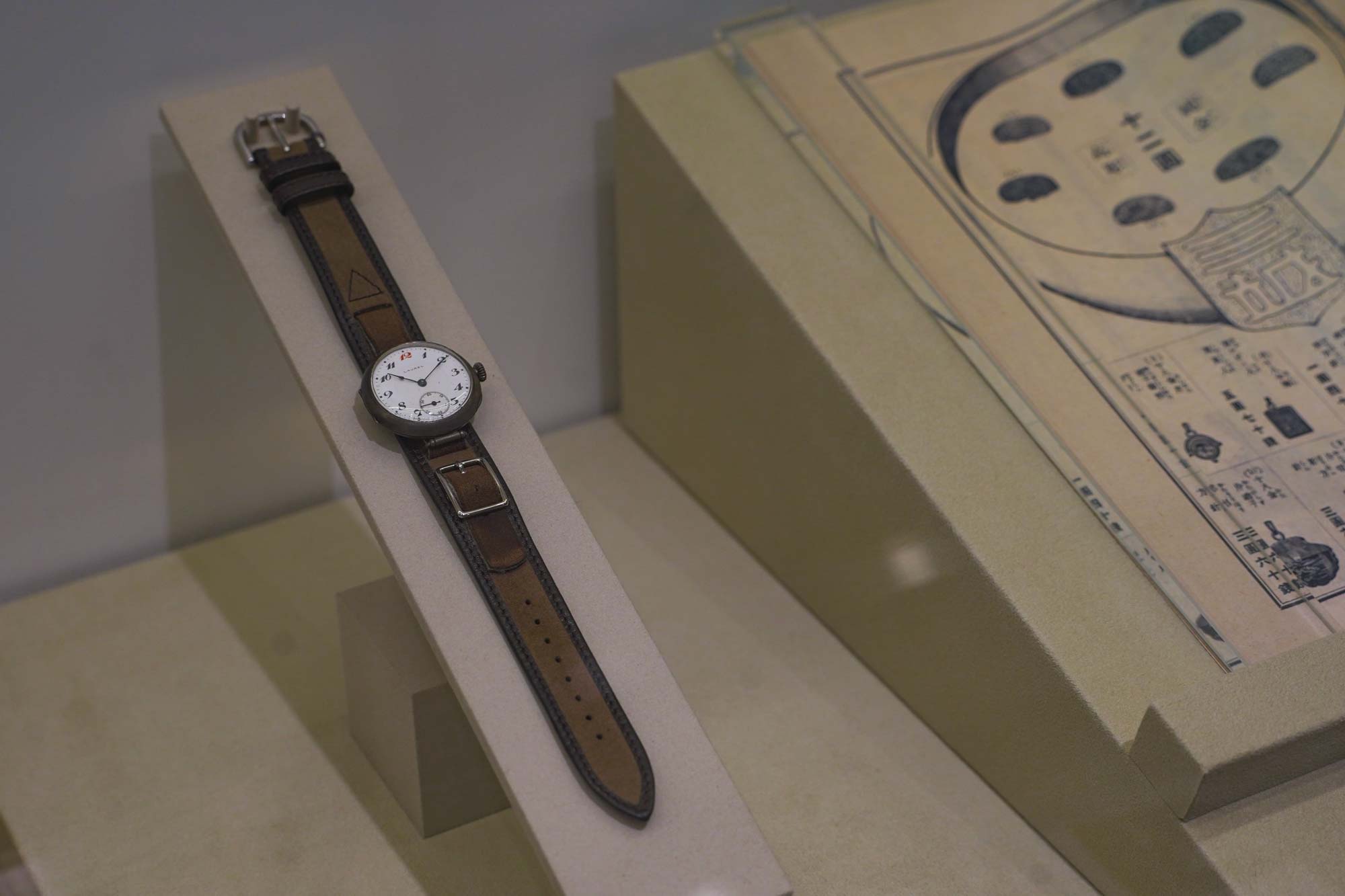

On September 1st, 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake struck Japan. It was a devastating natural disaster that resulted in over a hundred thousand deaths and fires that leveled Tokyo. Kintaro Hattori’s emerging business was also heavily impacted, but the company persisted, developing the first “Seiko” watch just a year later. As part of Mr. Hattori’s efforts to renew the company and give back to the ailing community, he released an ad to fix or replace pocket watches damaged or destroyed by the earthquake for free.

A move that seems mythical in terms of companies, the act of goodwill speaks to a brand that was greater than just selling goods. Pocket watches held more functional significance then than now for obvious technological reasons. Replacing them was truly a way to give back. That lump of pocketwatches is a tragic but potent symbol of this turning point for Seiko.

Part of what struck me, however, as a fan of the company, was that I didn’t know about this already. Though it likely has more local meaning, given the events that occurred, stories like this are the legends that build brands. Other companies in the world, say those who have some involvement in space flight, never miss the chance to remind you of it. I find it oddly charming that I had to go to a museum in Tokyo to learn this firsthand.

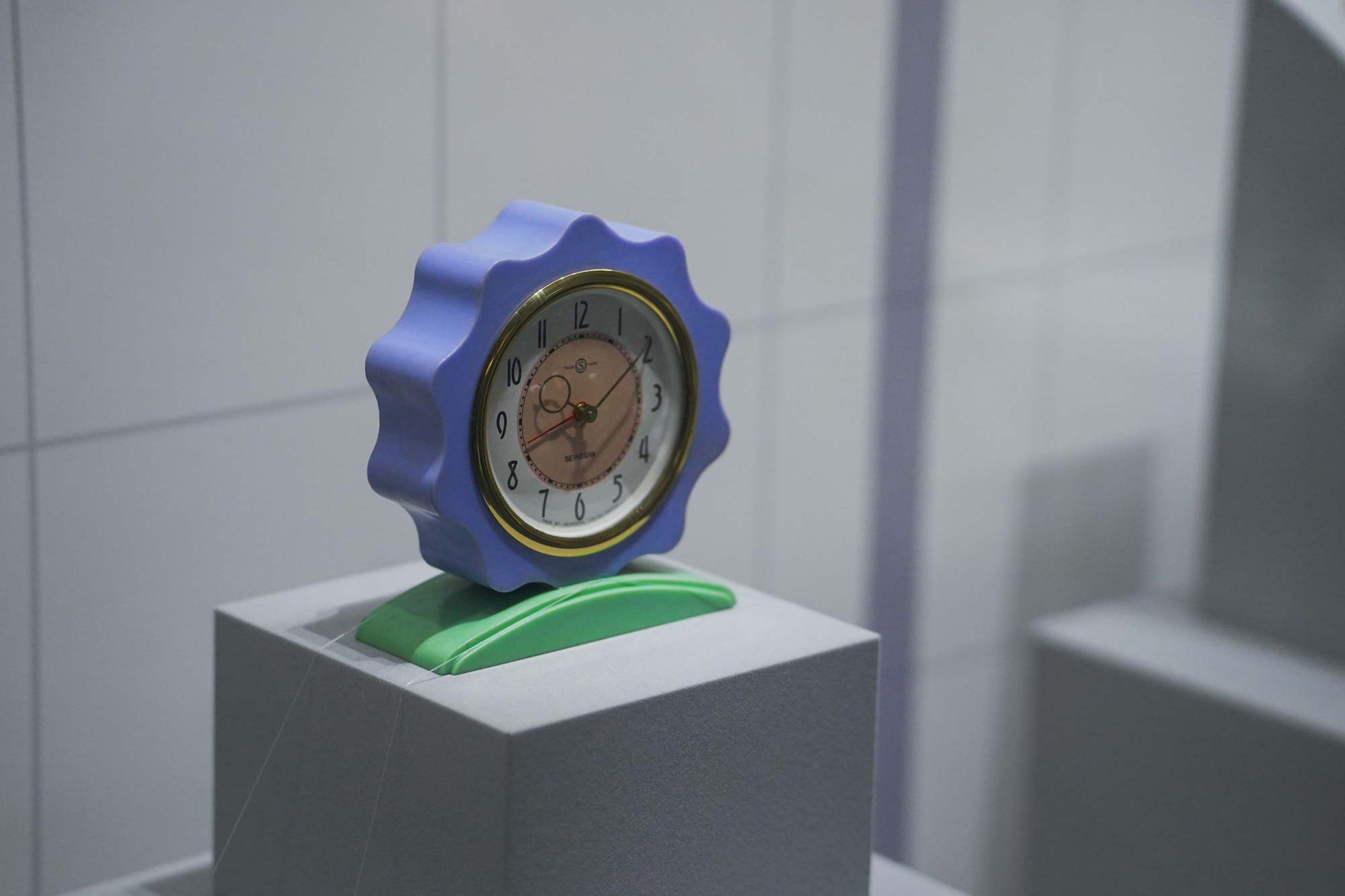

The other thing that stood out was not directly related to Seiko, but rather the history of telling time. Wadokei is a type of clock from the Edo period of Japan that is based on the seasons and the length of day. The clock features 12-hour units, six during the day and six at night. As the length of the day and night change, those units expand and contract. Functionally, this is executed by “regulating” the clock at sunrise and sunset. While difficult to synchronize, the poetic relationship between daylight, time, and the rhythms of how we live and work is profound, speaking to a more natural way of life.

Though the outcome is different, the heavy influence of nature and Japan’s micro-season structure are clear in Grand Seiko’s watches. While this was a cultural tie-in, nature is hardly Japan’s alone. But that a line can be drawn from a watch inspired by changing seasons to a method of living from centuries ago adds to the depth of meaning.

The Seiko Museum Ginza had floors of treasures to explore, which would take far too long to describe. It’s free and open to the public, so if you are a fan of Seiko and Grand Seiko and are in Tokyo, it’s a wonderful place to visit.